Alfred Russel Wallace statue by Anthony Smith

at the Natural History Museum in London

|

|

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913), a Biography

After publication of the Origin of Species in 1859, evolution by natural selection, biology’s great unifying concept, became famous as “Darwin’s theory.” First announced jointly the previous year, it is actually the Darwin-Wallace Theory. Nevertheless, Charles Darwin often called it “my theory,” while Alfred Russel Wallace, his partner and coauthor, graciously insisted “It is yours and yours only.” Wallace carried modesty to extremes, even calling his own book on evolution Darwinism (1889). Had he been more ambitious and less generous, evolutionary science might have become known as “Wallaceism.”

An explorer, zoologist, botanist, geologist and anthropologist, Wallace was a brilliant man in an age of brilliant men. Famous not only as cocreator of the natural selection theory, he was the discoverer of thousands of new tropical species, the first European to study apes in the wild, a pioneer in ethnography and zoogeography (distribution of animals) and author of some of the best books on travel and natural history ever written, including Travels on the Amazons (1869) and The Malay Archipelago (1872). Among his remarkable discoveries is “Wallace’s Line,” a natural faunal boundary between islands (now known to coincide with a junction of tectonic plates) separating Asian-derived animals from those evolved in Australia.

On weekend bug-collecting jaunts, the would-be adventurers discussed such favorite books as the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle (1845) and dreamed of exploring the lush Amazon rain forests of Charles Darwin’s ecstatic descriptions.

Another book also inspired them: Robert Chambers’s anonymously published Vestiges of Creation (1844), a controversial, literary treatise on evolution. Scorned by scientists, Vestiges championed the idea that new species originate though ordinary sexual reproduction rather than by spontaneous creation. Wallace and Bates decided they would comb the exotic jungles to collect evidence that might prove or disprove this exciting “development hypothesis” (only later known as evolution). When Darwin had embarked on his own voyage of discovery some 20 years earlier, he had had no such clear purpose in mind.

|

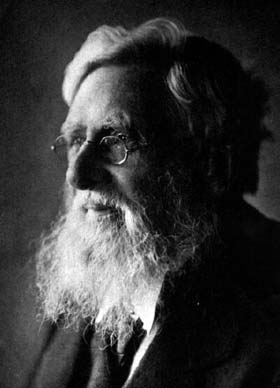

Brilliant, eccentric, and utterly his own man, Alfred Russel Wallace independently developed the theory of evolution by natural selection.

|

Science was not yet a well-established profession, and naturalists were often dedicated amateurs from wealthy families. When Darwin went on his circumglobal voyage, his father paid all expenses, even providing a servant to assist with his work. Wallace’s achievements are all the more remarkable, for he had to finance his expeditions by selling thousands of natural history specmens, mainly insects, for a few cents apiece. When his exploring and collecting days were over, Wallace struggled to support his family on author’s royalties and by grading examination papers. (He often said intelligence had nothing to do with getting rich, that “success at money-getting requires mainly impudence.“) Bates and Wallace reached Para, at the mouth of the Amazon, in May 1848; they collected and explored the surrounding regions for several months, then decided to split up. Wallace went up the unknown Rio Negro, leaving Bates to explore the upper Amazon regions. From 1848 until 1852, Wallace collected, explored and made numerous discoveries despite malaria, fatigue and the most meager supplies.

When he finally returned to rejoin Bates downriver, he found that his beloved younger brother had traveled across the world to join the adventure and had just died of yellow fever in Bates’s camp. Grief-stricken, exhausted and suffering from malaria himself, Wallace boarded the next ship for England. With him went his precious note-books and sketches, an immense collection of preserved insects, birds and reptiles, and a menagerie of live parrots, monkeys and other jungle creatures. In the midst of the North Atlantic, as Wallace suffered a new attack of malaria, the ship suddenly burst into flames. He was able to rescue only a few notebooks as he dragged himself into a lifeboat. Everything else burned or sank beneath the waves, and he later recalled:

I began to think that almost all the reward of my four years of privation and danger was lost . . . How many times, when almost overcome by ague, had I crawled into the forest and been rewarded by some unknown and beautiful species! How many places, which no European foot but my own had trodden, would have been recalled to my memory by the rare birds and insects they had furnished to my collection! . . . And now everything was gone, and I had not one specimen to illustrate the wild scenes I had beheld! The measure of Wallace’s enormous courage and resilience showed itself shortly after returning to England. With the insurance money he received for part of his lost collections, he immediately set out on a new expedition—this time to the Malay Archipelago

(1854–1862).

Wallace mastered Malay and several tribal languages, for he was intensely interested (as Darwin never was) in “becoming familiar with manners, customs and modes of thought of people so far removed from the European races and European civilization.” A self-taught field anthropologist, he made pioneering contributions to ethnology and linguistics and developed “a high opinion of the morality of uncivilized races.” He later recalled with satisfaction that while he lived among them he never carried a gun nor locked his cabin door at night.

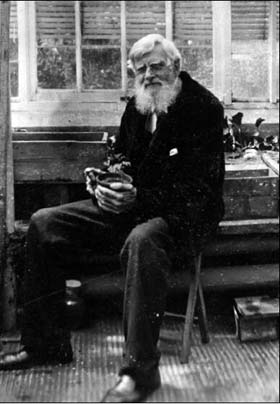

Naturalist, explorer, anthropologist, and founder of zoogeography, Alfred Russel Wallace was also the first European to observe orangutans in the forest.

|

|

In Malaysia (then known as the Moluccas) he tracked orang-utans through the deep forest, shot several for the British Museum’s collection and raised an orphaned infant orang in his field camp. Since local tribesmen regarded the red-haired apes as “men of the woods,” they were horrified when he shot and skinned them, convinced he would next want to add their own skulls to his collection. Wallace collected natural history specimens with an extraordinary passion:

I found . . . a perfectly new and most magnificent species [of butterfly] . . . The beauty and brilliancy of this insect are indescribable, and none but a naturalist can understand the intense excitement I experienced . . . On taking it out of my net and opening the glorious wings, my heart began to beat violently, the blood rushed to my head, and I felt . . . like fainting . . . so great was the excitement produced by what will appear to most people a very inadequate cause.

Wallace came to the idea of evolution not through artificia l selection of domestic animals, as Darwin had done, but through his observations of the natural distribution of plants, animals and human tribal groups and their competition for resources. Like Darwin, he had also been influenced by Thomas Malthus’s Essays On Population (1803), which he had read some years before.

In 1855, while in Sarawak, he composed “My first contribution to the great question of the origin of species.” Combining his knowledge of plant and animal distribution with Sir Charles Lyell’s account of “the succession of species in time,” he came up with a conclusion about when and where species originate. (“The how,” he wrote, “was still a secret only to be penetrated some years later.”) His paper “On the Law which has Regulated Introduction of New Species,” stated that: “Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a pre-existing, closely-allied species.” This preliminary conclusion, he knew, “clearly pointed to some kind of evolution.”

Published in an English natural history journal in September, 1855, Wallace’s “Sarawak Law” was generally ignored by the scientific world. When he expressed his disappointment in a letter to Darwin, “He replied that both Sir Charles Lyell and Mr. Edward Blyth, two very good men, specially called his attention to it.” Writing years later, Thomas Huxley said, “On reading it afresh I have been astonished to recollect how small was the impression it made.”

In February 1858, Wallace was living at Ternate, one of the Moluccan Islands and was suffering from a sharp attack of intermittent malarial fever, which forced him to lie down for several hours every afternoon:

It was during one of these fits, while I was thinking over the possible mode of origin of new species that somehow my thoughts turned to the “positive checks” to increase among savages and others described . . . in the celebrated Essay on Population by Malthus . . . I had read a dozen years before. These checks—disease, famine, accidents, wars, etc.—-are what keep down the population . . . [Then] there suddenly flashed upon me the idea of the survival of the fittest . . . that in every generation the inferior would inevitably be killed off and the superior would remain . . . and considering the amount of individual variation that my experience as a collector had shown me to exist . . . I became convinced that I had at length found the long-sought-forlaw of nature that solved the problem of the origin of species . . . On the two succeeding evenings [I] wrote it carefully in order to send it to Darwin by the next post . . .

It was this article, “On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type” (1858), that sent Darwin into a panic, convinced his friend Charles Lyell’s warning, that he would be “forestalled” by Wallace, “had come true with a vengeance.” Lyell and Sir Joseph Hooker, attempting to rescue their friend’s threatened prior claim, arranged to have Wallace’s paper published along with some of Darwin’s early drafts. The announcement of the Darwin-Wallace theory of evolution by means of natural selection was published in the Linnean Society’s journal in 1858; the following year Darwin wrote the Origin of Species and rushed it into print.

Wallace was informed of these developments after the fact and received a copy of Darwin’s book while still in Malaysia. When he returned to England in 1862, Darwin was anxious about Wallace’s reaction, and was relieved to discover his “noble and generous disposition.” Later Wallace maintained that even if his only contribution was getting Darwin to write his book, he would be content. But the fact remains that Wallace was not given an opportunity to exercise his nobility or generosity, since the joint publication was decided without anyone consulting him.

|

Young Wallace set off for the Brazilian rainforest, on a quest to find evidence for or against the idea of evolution.

|

In addition to the chronicles of his travels, Wallace turned out a remarkable series of books, all landmark contributions to evolutionary biology: Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection (1870), Geographical Distribution of Animals (1876), Island Life (1882) and Darwinism (1889). His idea of the living Earth as a single, complex system seems, in some sense, to have foreshadowed the Gaia hypothesis:

. . . there are now in the universe infinite grades of power, infinite grades of knowledge and wisdom, infinite grades of influence of higher beings upon lower . . . This vast and wonderful universe, with its almost infinite variety of forms, motions, and reactions of part upon part, from suns and systems up to plant life, animal life, and the human living soul, has ever required and still requires the continuous co-ordinated agency of myriads of such intelligences.

. . . there are now in the universe infinite grades of power, infinite grades of knowledge and wisdom, infinite grades of influence of higher beings upon lower . . . This vast and wonderful universe, with its almost infinite variety of forms, motions, and reactions of part upon part, from suns and systems up to plant life, animal life, and the human living soul, has ever required and still requires the continuous co-ordinated agency of myriads of such intelligences.

Unlike the cloistered, tactful Darwin, Wallace was imprudently outspoken about his religious and political beliefs. Outraged colleagues wanted to dismiss him as a “senile crank” for his strong advocacies of utopian socialism, pacifism, wilderness conservation, women’s rights, psychic research, phrenology, Spiritualism and his campaign against vaccination. Wallace replied he was not “brain-softening” with age, but had held many of these beliefs for 30 years.

Spiritualism strongly influenced his ideas on human evolution, causing him to differ with Darwin in 1869 on whether natural selection could explain “higher intelligence” in man. Wallace thought the human mind was supernaturally injected into an evolved ape from “the unseen world of Spirit.” He also rejected Darwin’s concept of “sexual selection,” which he dismissed as merely a special case of natural selection.

Although they remained friendly and mutually respectful, the y never really understood each other’s perspective.] Nevertheless, Wallace was called upon to be an honored pallbearer at Darwin’s funeral at Westminster Abbey.

In 1876, Wallace helped introduce a Spiritualist paper at the British Association’s scientific meetings, which apparently touched off the notorious Slade affair. He testified for the defense at the trial of Henry Slade and often defended other professional “spirit-mediums” who were accused of conducting fraudulent “psychic experiments.” In 1881, Wallace joined the Society for Psychic Research; he headed the Land Nationalisation Society in 1882 and openly declared himself a Socialist in 1890. Some of his admirers had recommended he be appointed director of the proposed new park at Epping Forest, but Wallace immediately lost the position by stating that he would keep the woodland exactly as it was for future generations, allowing no restaurants, hotels or other concessions. Darwin started a petition among scientists to get Wallace a civil pension, but botanist Sir Joseph Hooker and others objected to appealing for government funds on behalf of “a public and leading Spiritualist.” However, Darwin and Huxley prevailed and Wallace got his pension. (Huxley, though differing with Wallace on many issues, assured him that he would never seek a Certificate of Lunacy against him!)

In his last book, Social Environment and Moral Progress (1913), Wallace catalogued the horrors of the urban poor, colonial exploitation and “reckless destruction of the stored-up products of nature, which is even more deplorable because more irretrievable.”: It is not too much to say that our whole system of society is rotten from top to bottom, and the Social Environment as a whole, in relation to our possibilities and our claims, is the worst that the world has ever seen [because of] our system of Individualist Competition.

Sir David Attenborough unveils statue of Alfred Russel Wallace

at London’s Natural History Museum.

|

|

He was furious when apologists for the status quo told him society needed no safety net for its poor or infirm, since, according to the “law” of natural selection, they ought to be eliminated. “Having discovered the theory,” he fumed, “it is rather amusing to be told . . . that I do not know what natural selection is, nor what it implies.” Eugenists who sought to regulate human breeding for selective improvement he considered “dangerous and detestable . . . sure to bungle disastrously.”

Influenced by the socialist Henry George, Wallace urged a policy of land nationalization and an economy in which “all shall contribute their share either of physical or mental labor, and . . . every one shall obtain the full and equal reward for their work. [Then] the future progress of the race will be rendered certain by the fuller development of its higher nature acted on by a special form of selection which will then come into play.” What “special form of selection” might be the salvation of humanity? Wallace argued that human populations produce many more males than females, but in his day young men were dying by the millions. Alcoholism, dangerous occupations and particularly the frequent wars left Europe with a huge proportion of unattached women. But under a just and nonmilitaristic social system, Wallace predicted, the number of males would rise dramatically, until they greatly outnumbered women:

This will lead to a greater rivalry for wives, and will give to women the power of rejecting all the lower types of character among their suitors . . . [The well-educated, enfranchised, responsible] women of the future [will be] the regenerators of the entire human race . . . in accordance with natural laws. . . .

Wallace’s special hope for the salvation of mankind, then, was none other than “sexual selection,” one of Darwin’s favorite mechanisms for explaining the evolution of man—which Wallace had always insisted did not exist! However, Wallace added a twist to Darwinian sexual selection: an explicit acknowledgement of the large evolutionary effects of a slight change in sex ratio, a surprisingly modern way of thinking about populations. During the 1970s and 1980s, Alfred Russel Wallace become a hero among disaffected academics and independent scholars. They saw in him a brilliant scientist, working outside the establishment, scrabbling for a living, snubbed by those with wealth and position, persecuted for unpopular social views—possibly even deprived of his rightful place in history. Yet Wallace was morally triumphant as a great human being and fearless truthseeker, cheerful, optimistic and productive into his ninetieth year.

In 1985, the British Entomological Society, of which Wallace was once president, launched a series of major expeditions to study the insects of the world’s tropical rain forests. They called it “Project Wallace.”

—Richard Milner

Return to Wallace home page

Retirm to Darwin Live home page

|